Nine Sols, SquareSoft’s Summer of Adventure & The “Souls-ification” of the Metroidvania Sub-Genre

Nine Sols, SquareSoft’s Summer of Adventure & The “Souls-ification” of the Metroidvania Sub-Genre; an observation on the state of the scene.

UnexpectedGames

UnexpectedGames

Just a friendly bear who works in financial reporting that would rather be playing, writing or talking about video games. https://twitch.tv/unexpectedenemy

Nine Sols, SquareSoft’s Summer of Adventure & The “Souls-ification” of the Metroidvania Sub-Genre; an observation on the state of the scene.

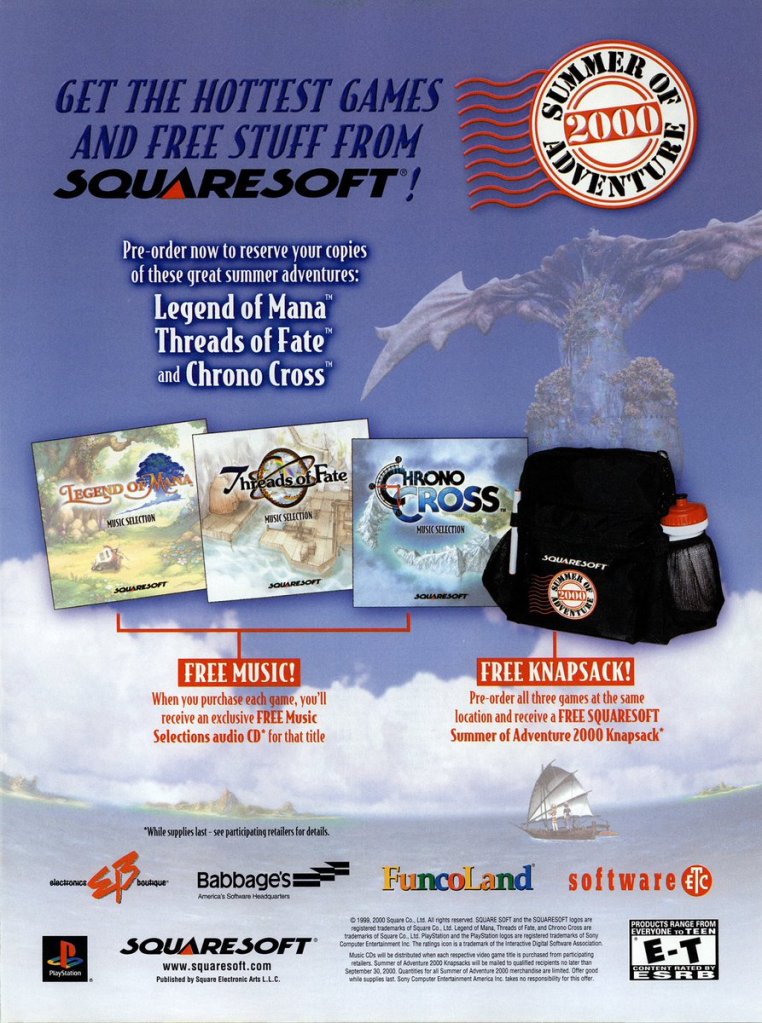

Remember SquareSoft’s “Summer of Adventure” promotion back in 2000? If you purchased Legend of Mana, Threads of Fate and Chrono Cross from participating retailers, you could receive free soundtrack samples for each game, in addition to a knapsack to commemorate the event (I’m pretty sure I got the “FREE Music Selections audio CDs”, but I don’t ever recall seeing that knapsack). My brother and I grew-up playing SquareSoft RPGs on the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) and we more or less remained fans of both the developer and genre well throughout the decades since. This era of SquareSoft was particularly interesting in retrospect, however. While I do appreciate these three games more so today than I did back when they first released, they certainly represented a shift in design philosophies for their time. Excluding Legend of Mana (to a degree), none of these games had traditional leveling/progression systems. They almost felt like they were more influenced by SquareSoft’s very own SaGa series than the immediate games that came before them, considering how unconventional they were. Two of these games (Threads of Fate and Chrono Cross) traded traditional experience points to level-up for individual stat increases instead, for example. On top of that, if I recall the temperature correctly at the time, they were all rather divisive. The Legend of Mana was a huge departure structurally from its predecessors (and also very easy, at least on the default difficulty). Chrono Cross has never lived down the fact that it was simply the follow-up to one of the most cherished RPGs of all time, Chrono Trigger (it also felt more tonally similar to Xenogears, which probably didn’t do it any favors). Threads of Fate, though? Well, you had Brave Fencer Musashi before it, a cult-classic in its own right, although not entirely related to it. Before Square’s Summer of Adventure, however, my brother and I had already taken a vacation or two a few years prior.

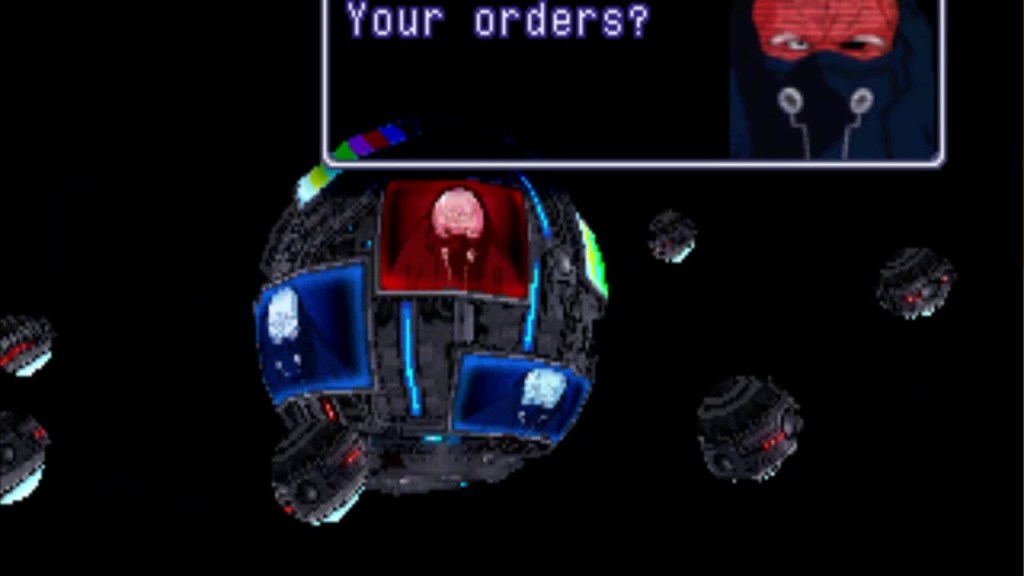

It was likely the summer of 1998. School is finally out, so three months of uninterrupted gaming for my brother and me is on the horizon. We get home from our last day at school, change out of our uniforms into something more comfortable, fire a TombStone Pizza into the oven, and start a playthrough of Wild ARMs (WA) for the PlayStation 1 (PS1). Our goal? To finally defeat “Ragu O Ragula” (who we named “Ragu spaghetti sauce”) without using the duplicator glitch. We were going to beat the ultimate secret boss legit this time! If you’re not familiar with the series, WA is a 2D, top-down, turn-based RPG that feels like a spiritual successor of sorts to the Lufia games on the SNES. While the combat and progression systems weren’t particularly innovative for its time, each character had Zelda-like tools (like bombs to blow-up walls or a hook-shot to cross gaps), which made dungeon traversal and exploration more interesting compared to its contemporaries. In WA, the main antagonists are a group of villains called the “Quarter Knights”. Each member of the Quarter Knights has their own distinct personality and serve some greater purpose in the game’s story. You fight each member of this group individually over the course of the game, which made them feel more memorable given their collective efforts to thwart the heroes. Ever since the first WA, I’ve been obsessed with well-defined groups of “bad dudes” in videogames. Although it’s not quite the same, a few years later in SquareSoft’s Xenogears, I would be introduced to a mysterious organization called the “Gazel Ministry”. If you’ll excuse minor spoilers for a 20+ year-old game, at some point you learn that people from this group have been digitally preserved in a machine called the “SOL-9000”. The physical representation of these characters is just a bunch of big-brained, masked-faced individuals projected onto an amalgamation of computer screens. It was the coolest and while many games have had memorable groups of villains since, a recent game from Taiwan has completely captured my Sol.

Nine Sols, developed by Red Candle Games, is a 2D Metroid-like with an emphasis on counter-based combat. According to the developers, it was heavily inspired by Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, Hollow Knight and Katana ZERO. Considering the developers previous horror-focused releases, Nine Sols is quite the departure in terms of tone, setting and genre. The game blends sci-fi with Taosim and Far Eastern mythology described as “Taopunk”. In Nine Sols, a race of cat-like people left their home world due to a virus in hopes of survival amongst the stars. Although there are many twists and turns along the way, the game primarily takes place on an advanced space station of sorts called “New Kunlun”. It’s here where members of the titular “Nine Sols” have been assigned roles and locations on the station based on their expertise and earthbound titles. These “Sols” are essentially the main antagonists, a group of sophisticated individuals who the main character, Yi, must take down in order to exact his revenge and achieve his goals. Although the interior of the ship can feel a bit claustrophobic and clinical in terms of its overall design and aesthetic, each area is thematically centered around one of these “leaders”.

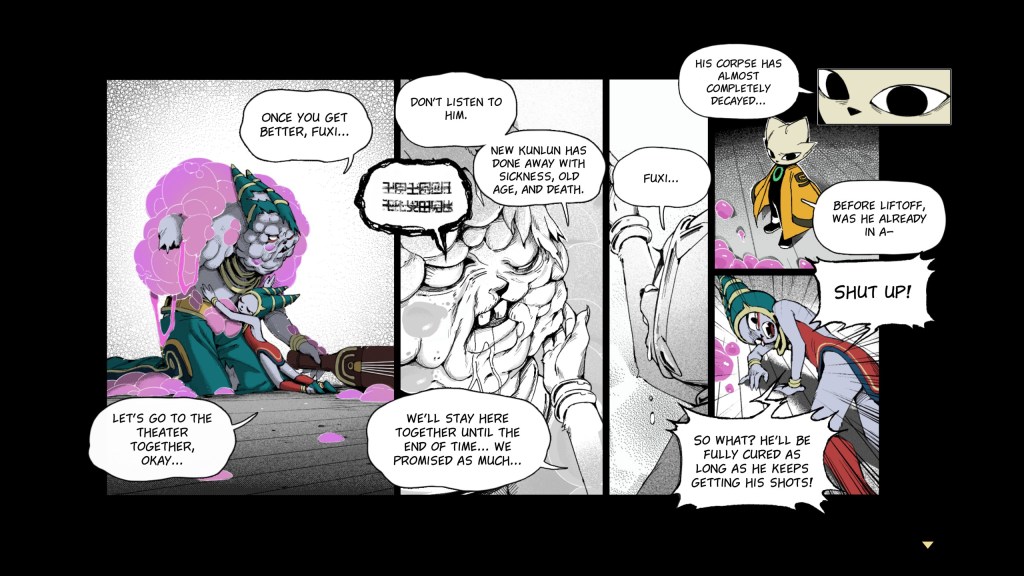

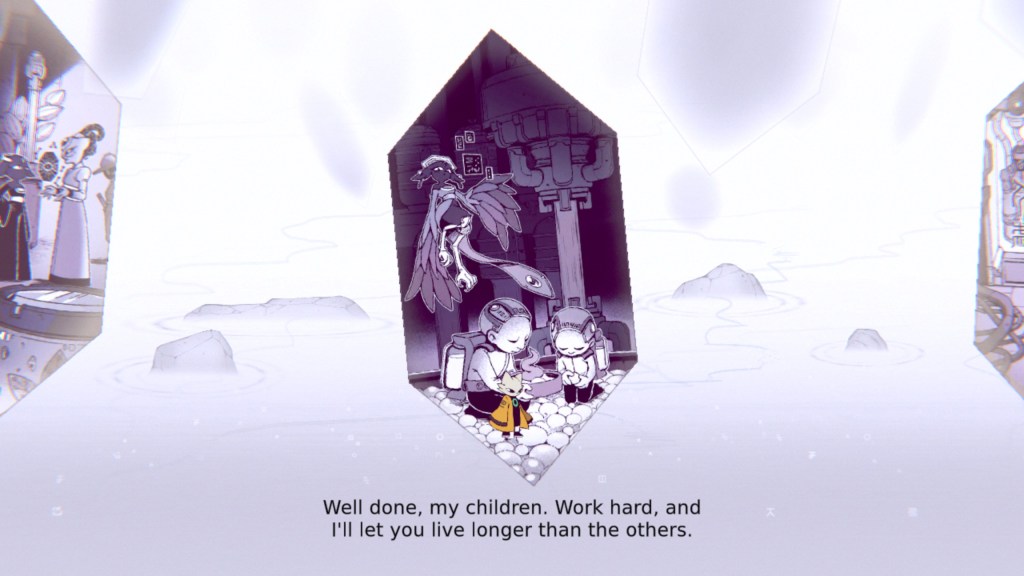

In one instance, you’ll find a warehouse sector full of artifacts pillaged from the character’s home world ruled by an elderly archivist of sorts. In another instance, you’ll find yourself in an entertainment district where all of the rich and privileged citizens dance and party their final days away, lead by royal siblings who just couldn’t care less. One of the Sols, named Kuafu, is an engineer you befriend after beating the first major boss. This big, fluffy cat is in charge of supplying power to the space station, but because the two characters share some sort of history together, he ultimately assists Yi on his quest by providing the main character with weapon upgrades. Establishing the “presence” of an antagonist seems like a difficult prospect in videogames, even today. Generally speaking, villains are often sequestered in a far-away “castle” only ever appearing during pivotal story moments or cut-away cinematics where evil plans are being discussed after “meanwhile…” is written in white text on a black background. In Nine Sols, when you enter a new area of the space station, you’re almost always greeted by the Sol inhabiting that section via a Metal Gear Solid-like codec screen where Yi and the antagonist exchange not-so-nice pleasantries. As you encounter more Sols and defeat them in battle, you’re presented with these beautifully illustrated vignettes showcasing their past where you learn more about how they rose to power. It’s super compelling stuff.

Visually, the game uses a beautiful mix of 2D, hand-drawn sprite-work and 3D polygonal backgrounds. The lighting is also very impressive. You’ll often pass computer screens and other contraptions in the background that flash and illuminate the surroundings adding a nice layer of depth to the environments. Characters are expressive and animated, particularly in their dialogue portraits, too. As if the game wasn’t stylish enough already, there are manga-style panels to illustrate important scenes, particularly before/after boss battles. Additionally, there are these beautiful flashback sequences that are seamlessly integrated into the game. As Yi explores certain areas, he’s reminded of his time spent with his sister, Heng, and they are some of the more touching moments in an otherwise dark and depressing story. Considering the developer’s legacy, having been known for horror games previously, Nine Sols is a fairly violent and horrifying experience. There’s one scenario in the game involving a particular Sol that’s more or less a horror sequence with jump scares and twisted imagery. Nine Sols clearly had a vision as it all somehow feels super cohesive despite the hybrid of art and presentation styles at play here.

The cast in Nine Sols is extremely memorable. There’s Shuansuan, an “Apeman” (human), who you save during the introduction sequence. Shuansuan is crucial to Yi’s personal development and some of the most heart-warming and interesting conversations in the game take place between the two. Shennong, another Apeman, begrudgingly joins you and shares stories and drinks with you when you feed him poisonous foods (which increase your maximum health bar). There’s even a home base where you often return to in order to advance the story, but it’s here where you’ll get to know everyone more based on the amount of optional content you engage with. By completing side quests and finding particular items, you’ll befriend each character and learn more about their pasts, perspectives, philosophies and more. Finally, while the game isn’t fully voice-acted, the characters will speak a word or two at the start of particular sentences, which is a common technique used in a lot of games that might not have the budget for every line to be spoken (I’d like to think it was more of a stylistic choice in this case). The writing/localization seems quite excellent, too.

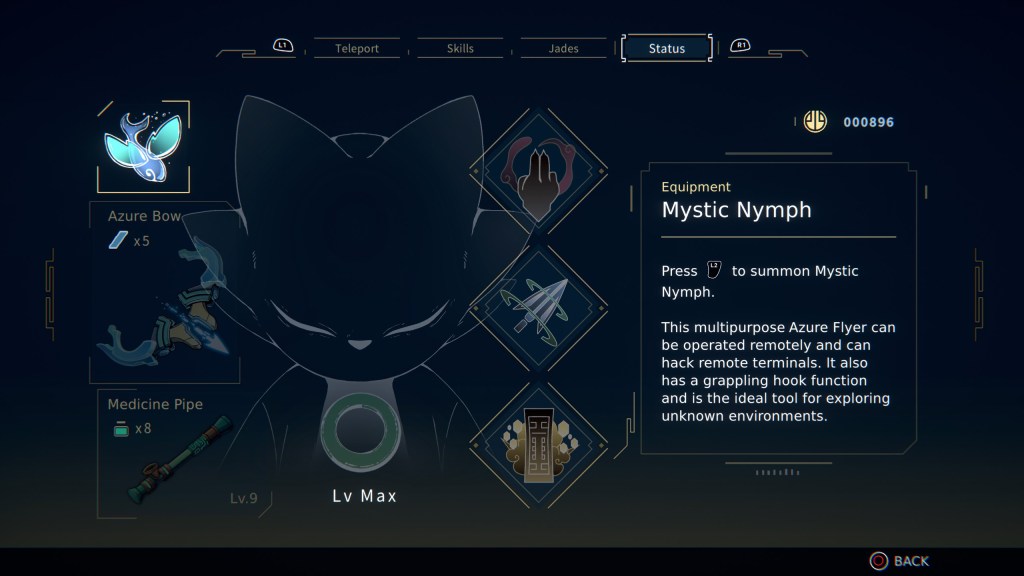

Nine Sols doesn’t do anything particularly new in terms of being a Metroidvania/Metroid-like. It’s fairly by-the-books in terms of its overall structure and design. The map is divided into segments, but the entire game is interconnected with shortcuts and wrap-arounds. You have a familiar called the “Mystic Nymph”, which is a digital bird-like companion who can access out-of-reach switches to lift gates or move platforms. While you do unlock the ability to fast-travel mid-game, it can become a bit difficult to navigate the environment in the early portions of the adventure. The main objective is typically made clear to the player, but I did find myself getting lost and retreading parts of the map until I exhausted all available paths. With that said, you do have to earn the ability to see what you’re missing for each segment of the map by discovering helper robots in each region. You can either pay for their map details or destroy them and steal their chip. After you obtain their data, each map will show you how many available treasure chest you discovered and how many unique enemies you’ve destroyed, for example.

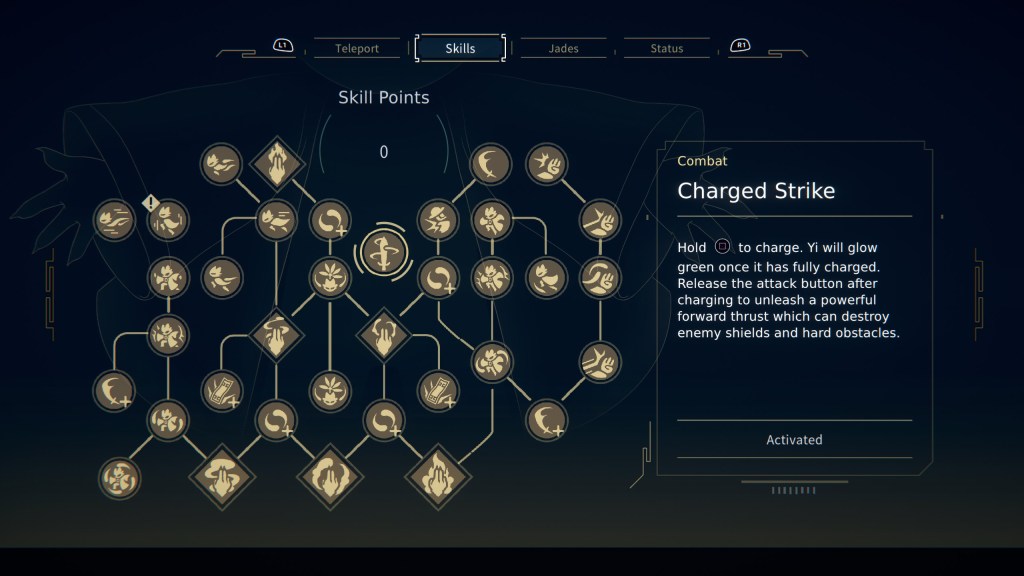

Although you increase your maximum health through the aforementioned method with an NPC, you do gain traditional experience points by defeating enemies. When you “level-up”, you’re granted a skill point which can be used to unlock new abilities (there are also special items you can discover which grant you skill points immediately). You’ll learn core skills at certain points in the game such as gaining the ability to perform charged strikes, which can break enemy barriers and other environmental gates. In addition to this, you’ll also learn an air dash and the coveted double jump (which is also unlocked towards the end of the game and has become somewhat of a trend in Metroid-likes as of late). A lot of these core skills have upgrades on the skill tree that further enhance their properties. Then there are the “Jades”, which are basically the “Charms” from Hollow Knight that grant you passive/active bonuses (think of them like accessories in an RPG). Each Jade has a cost to equip, but by collecting/purchasing additional “Computing Power”, you can customize Yi with a variety of Jades, making a customized “build”, if you will. One of the Jades impacts your healing animation, for example, shortening the amount of time it takes to heal yourself so you can get back to the fight uninterrupted. Another Jade increases the gold earned when defeating enemies. Many of the Jades are specifically engineered to enhance your countering/parrying capabilities, however, which is a system the developers clearly wanted players to engage with and master.

What differentiates Nine Sols from other games in the sub-genre is its focus on counters/parries. The developers weren’t kidding when they said Sekiro was an inspiration to them, at least in terms of the combat system. While there’s an easier “Story” mode, I played through the game on Standard difficulty, which honestly felt like the game’s “Hard” mode. It’s a brutal, unyielding game on this difficulty, particularly when you’re up against one of the game’s many bosses. You absolutely have to engage with and master the ability to block and parry enemy attacks. If you guard a regular attack, you gain a “Qi charge”. At some point, the game introduces you to un-blockable attacks where an enemy becomes engulfed in a green flame before they attack. To counter these hard-hitting attacks, you’ll learn an aerial kick or what’s called an “Unbounded Counter”, both of which grant you Qi charges when successfully performed. A Qi charge lets you use a “Talisman” attack; a glyph that you can apply to enemies when you dash through them to cause major damage. There are a handful of Talisman attacks including one that will automatically explode after a certain amount of time and another that you can manually detonate (which is what I ultimately used near the end). If you don’t “spend” your built-up Talisman attacks, you’re sort of wasting opportunities to deal massive damage to an enemy. It creates these sort of risk/reward combat scenarios where you have to simultaneously play defensively and be the aggressor.

Once you meet the game on its own terms, countering/parrying becomes this natural flow state that feels supremely rewarding. The game gives you a lot of options to overcome its many challenges, but you have to be ready to commit in order to make any sort of headway against your enemies. I completed Nine Sols on Standard difficulty at around 35 hours. I beat the true final boss with all side quests completed and with everything collected, upgraded and maxed out. At the time of writing this, Nine Sols is my current game of the year (GOTY) for 2024 and quite possibly my favorite Metroid-like/Metroidvania I’ve played from the past decade. While the sub-genre has mostly stayed true to its roots, a certain popular series of games, for better or worse, has had a major impact on the Metroid-makers of today.

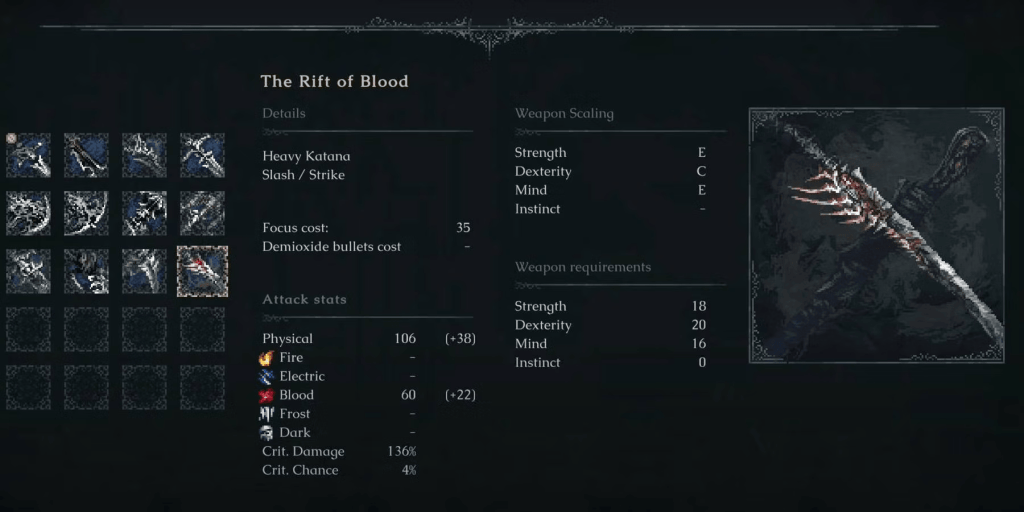

I was recently back home in Pennsylvania to see my father before he passed. While I was there, I also spent a lot of time with my brother. Most of our time together, when not in hospice with our dad, was simply spent playing games and catching-up. We had to keep some semblance of normalcy, otherwise we would begin to spiral. Over the past year or two, my brother has recently been on a Metroidvania-kick. He even finished a few games before I did, including Hollow Knight, which was a shock, considering his disinterest in most of the modern video game landscape. He was currently playing a game called The Last Faith, so I watched him play it and we started talking about the state of the scene. It was yet another 2D Metroid-like, inspired by Blasphemous and other games in the sub-genre, but it also clearly took inspiration from another cult-classic behemoth; Bloodborne (or Souls-like games in general). I was surprised/not surprised to see a status page in a Metroidvania that felt like it was completely ripped out of one of From Software’s games. The Last Faith, of all things, has weapon scaling based on how you distribute your stats! The character status sheet in The Last Faith also didn’t look too different from another recent 3rd-person Souls-like game, Neowiz’s Lies of P. Despite the game’s quality, and if you’ll excuse the pun, it’s all perhaps a bit too “on the nose”, but I digress.

I’ve always believed the Metroidvania sub-genre to be split into two well-defined categories; Metroidvanias and Metroid-likes. While both categories share similarities and are arguably interchangeable, there are distinct aspects that differentiate the two types of games. I think it’s fair to say that most people consider Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (SotN) to be the “all-father” of Metroidvania games as it took the “search-action” elements of Super Metroid and infused it with traditional RPG traits; experience levels, equipment and enemy drops (loot). While there were still “HP Max-Up” items to collect and upgrades/abilities that let you access new areas, à la Super Metroid, the traditional RPG character progression sort of took precedence. A Metroid-like is mostly a search-action game that doesn’t have those traditional RPG elements; no equipment or leveling of the sort. Ultimately, these descriptors are silly, as many games today continue to blur the lines in unconventional ways (see Capcom’s latest Kunitsu-Gami: Path of the Goddess, for example), but conversationally, it’s a fun discussion to have amongst enthusiasts.

As of August of this year, I’ve played and finished a half dozen or so Metroidvanias/Metroid-likes, including Nine Sols, Hollow Knight, Blasphemous I and II, Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown, Bō: Path of the Teal Lotus and more. From my observation, it feels like a lot of these games have leaned more into environmental storytelling and lore found in item/bestiary descriptions to tell their story (and that’s on top of the aforementioned “retrieve your souls after death” mechanic that’s infected a lot of these games, including Nine Sols, like it’s the beast plague from Bloodborne). From Software’s games, particularly their Souls titles, are known for meticulously detailed environments, world-building and lore. You see that large stone over there underneath that inconspicuous tree? That’s where Ethan, the Kingslayer laid his beloved dog to rest after the Charcoal Plague made his mutt go mad and killed his only remaining child. How did I know that? Well, if you look closely under that tree, there’s a bone near the gravesite that you can’t interact with. In the surrounding area, however, there’s a rabid dog patrolling the woods who has a 10% drop rate for a bandana that you can equip (with near-zero defense properties), but its item description reads, “Property of My Most Beloved Beast, Beatrice”. I feel like where a year or two away from seeing stuff like this in modern-day Metroidvanias, if it hasn’t happened already. Okay, maybe I’m exaggerating a bit here.

I finally played through Hollow Knight this year and I had no clue what was happening in the game until my brother showed me part of a lore video on YouTube. Is it my fault for playing too many games at once and not giving Hollow Knight the time it deserves? Perhaps. But I think I was simply never wired for this type of exposition, particularly when it came to playing Metroid-likes. SotN and Koji Igarashi’s Castlevania games since have sort of trained my brain in a way that’s not indicative of how a lot of these games are made today. For one, in SotN, Alucard could perform a back-dash. Every kid I knew who played the game growing-up got around the castle much quicker by back-dashing down corridors. This maneuver sort of lent itself to a “steamrolling” playstyle I’ve since inherited and I fear it’s something my brain cannot undo. I would also be remiss if I didn’t mention the impact Blizzard’s Diablo has had on the industry as a whole. Diablo II was the first time I can recall hearing the term “gems” or the phrase “socketing your gems”. Gems in Diablo II were an additional way to add properties to your equipment to further customize your character and differentiate your “build”. Although I’ve been focusing on From Software’s Souls releases as the basis for my modern-day Metroidvania analysis, a lot of the inspiration here is still arguably derived from Dungeons & Dragons, Wizardry, Ultima and, well, Diablo. Most Metroidvanias are RPG-like in nature, so it’s no surprise that the idea of “slotting accessories into your character” has become a standard for games in this sub-genre. You want to make a Metroid-like/Metroidvania today? You better have 3-4 rows of charms, beads, omamori, jades or some other gem-adjacent material to customize your character.

Over the years, I’ve found myself engaging with Metroid-likes similar to how I’ve approached other 2D action-platformers in the past. In general, 2D platformers aren’t typically the type of experiences where I will stop, sit and ponder whether or not the statue in the background has some sort of vital meaning to the plot. That’s not to say games like Super Metroid and SotN didn’t make attempts at this style of storytelling. Super Metroid starts in a derelict space station with dead bodies strewn on the floor and not a single piece of dialogue is spoken. I also recently learned that there’s a bird nest in the Outer Wall area in SotN where baby birds get fed, grow, and leave their nest over time. There’s also that infamous sequence in Super Metroid where a bunch of animals show the player how to wall-jump, which was the perfect marriage between environmental storytelling and providing menu-less, organic tutorials to players. I feel that a lot of Metroidvania-makers today are taking this environmental storytelling approach to heart more so than the developers of yesterday did. I do wish more games in this sub-genre would be a bit more deliberate in their storytelling, however. It’s why I prefer Nine Sol’s approach over other recent games; the story setup is made abundantly clear within the first hour of the game and while there’s still world-building found in terminals and such, you’re not scrambling through monster descriptions in a menu to go “Ah, so that’s what’s going on!”.

Metroid-likes/Metroidvanias are a dime a dozen today, but that hasn’t always been the case. There was a time when Igarashi and company were the only ones making games like SotN. Similar to how SquareSoft evolved and experimented with their own RPGs back in the early 2000s, perhaps the indie developers of today are doing the same thing by implementing new ideas into a tried and true formula. While I certainly “like my Metroidvanias a certain way”, it’s cool to see teams from all over the world driving their stake and taking their claim in what’s now considered a very crowded space. What did Dracula say again back in 1997? “Perhaps the same can be said of all… videogames“.

Bye Forever

-Matty

2 Comments »